Liberalism’s Best Enemy: A Tribute to Alasdair MacIntyre

by Matthew McManus

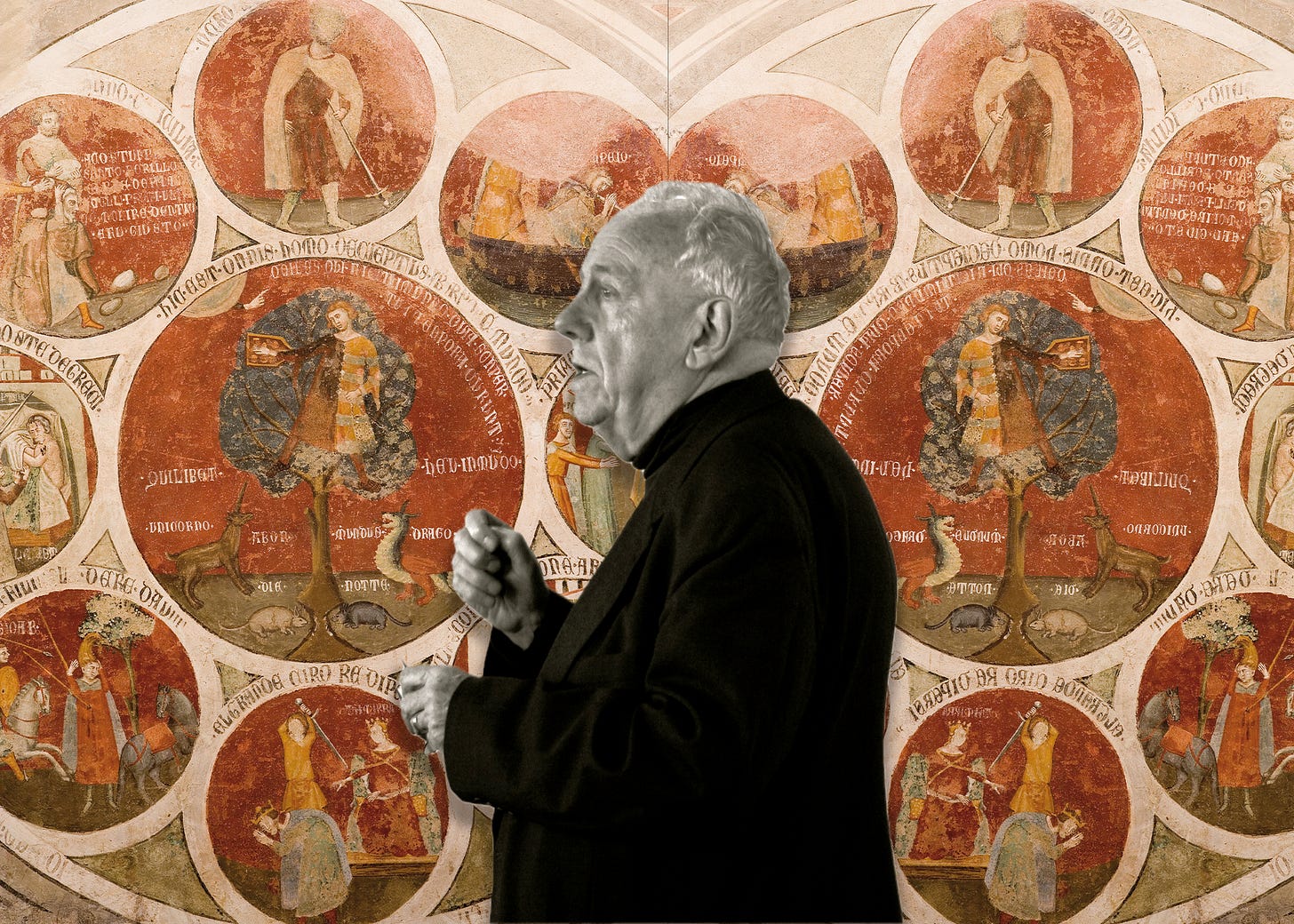

Alasdair MacIntyre died early this spring. A giant in the field of moral philosophy, the tributes were appropriately voluminous and eclectic. Perhaps no other thinker in our time could have solicited grief and respect from Jacobin to First Things. The laurels are well deserved. MacIntyre was an original, and we will not see his like again. No one else recognized and affirmed deep philosophical and spiritual connections between Aristotle, Aquinas, and Marx, let alone made their integration feel both natural and vital. Combining analytical philosophy’s rigor with continental breadth and spiritual seriousness, he will be an inspiration to generations hungrily turning the pages of After Virtue.

MacIntyre’s work went through a variety of phases, and debates rage about how much of his thought is continuous and how often it broke from earlier positions. There was, however, one constant to his writing: MacIntyre unrelentingly condemned both liberalism and capitalism. This evolved depth and salt but never wavered. In this, MacIntyre is quite distinct from other philosophers once lumped under the label “communitarian.” Michael Walzer, Sandel, and Charles Taylor have long offered left and “liberal socialist” critiques of liberalism. But they made their peace with it some time ago, and the criticisms have largely been internalized into the liberal family. Not so with MacIntyre, who until the end insisted that another form of politics could, and must, be possible. In this piece, I will pay tribute to MacIntyre by briefly summarizing some of the core tenets of his critique of liberalism and its influence. I believe that a radicalized liberalism can answer them. But this is not to deny their power and provocation.

Liberal Ethics, Capitalist Perversion

MacIntyre’s critique of liberalism is sharper than his erstwhile “communitarian” kin for a simple reason: he fully integrates its ethics with the capitalist mode of production. Social democrats and liberal socialists like Walzer and Sandel think it is possible to bracket the achievements of liberalism from capitalism, saving the former and radically transforming the latter. MacIntyre was far more skeptical. Indeed, he often associated this conviction with a kind of utopian naivete of the sort both liberals and socialists, as heirs to the meliorist Enlightenment, found so irresistibly tempting.

MacIntyre’s critique of liberalism is sharper than his erstwhile “communitarian” kin for a simple reason: he fully integrates its ethics with the capitalist mode of production.

MacIntyre began his career as an eclectic Marxist and socialist. Contrary to some anti-Marxists who see him as breaking with this tradition, as late as Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity (his final great work), MacIntyre insisted that there are lessons in Marx that we are doomed to relearn again and again. In Marxism and Christianity, MacIntyre insists that Marxism carried over much of the spiritual and philosophical insights that had characterized Christianity at its most vital.

This went further than just an emphasis on the needs of the wretched of the earth. By challenging the naturalization of the market and its laws, Marxism revealed the extent to which bourgeois ideologies reify our societies and the market domination thereof. The preeminent ideological system offering apologias was, of course, liberalism, which endlessly insisted that we had reached the end of history (which was basically McDonald’s). For the young MacIntyre in Marxism and Christianity, “liberalism…simply abandons the virtue of hope. For liberals, the future has become the present enlarged.” More malignantly, liberalism opened the door to a kind of nihilism that neither Christianity nor Marxism could abide. Liberals had unquestioningly accepted Hume’s dictum that “facts are one thing, values another—and that the two realms are logically independent of one another.” However much they tried to avoid it, liberals came to subjectivist conclusions. For “the liberal, the individual being the source of all value necessarily legislates for himself in matters of value, his autonomy is only preserved if he is regarded as choosing his own ultimate principles, unconstrained by any external consideration. But for both Marxism and Christianity only the answer to questions about the character of nature and society can provide the basis for an answer to the question: ‘But how ought I to live?’”

In the end, MacIntyre claims that all of liberal philosophy’s attempts to develop a morality are in vain.

By the time of his classic, After Virtue, MacIntyre was increasingly skeptical that orthodox Marxism had the answer to the question of how we ought to live, even if he stresses that Marxism remains “one of the richest sources of ideas about modern society…” For MacIntyre, liberal moral theorizing inevitably becomes co-extensive with the vulgarized forms of rationality spread by the market. Liberal thinkers from diverse traditions, from utilitarians to Kantians, all try to ground an objective morality in strange places; from hedonistic utility maximizers who are nonetheless to put their own gratification aside to pursue aggregate well being, to Kant’s moral legislators who are free to will their own laws but should only “freely” will those laws that accord with practical reason. In the end, MacIntyre claims that all of liberal philosophy’s attempts to develop a morality are in vain. They reduce down to the morality of the case register: the emotivist conviction that morals are just a matter of personal tastes, with an inclination to be St. Benedict or St. Trump being equally valid. That is when they don’t lead to the Nietzschean will-to-power and domination. In a word, the liberal Enlightenment project was a great big failure:

The problems of modern moral theory emerge clearly as the product of the failure of the Enlightenment project. On the one hand the individual moral agent, freed from hierarchy and teleology, conceives of himself and is conceived of by moral philosophers as sovereign in his moral authority. On the other hand the inherited, if partially transformed rules of morality have to be found in some new status, deprived as they have been of their older teleological character and their even more ancient categorical expressions of an ultimately divine law.

Instead of all this, MacIntyre looks back to Aristotle (and eventually Aquinas and other Christian fathers) to provide moral alternatives to the vulgar society described so vividly by Marxism. But it is to be a redescribed “revolutionary Aristotelianism” that is, in many respects, very modern. For instance, MacIntyre largely accepts that we cannot simply go back to the pre-modern metaphysical worldview out of which Aristotle’s teleology and Christian ethics emerged. Any attempt to save their insights will have to secularize and modernize them in many respects.

MacIntyre insists that critics must learn from and admire the richness of the liberal tradition while liberals must accept that theirs is only one moral tradition amongst many.

Later books like Whose Justice? Which Rationality? and Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity attempt to do just that. In these works, his disposition towards liberalism softens somewhat. In Whose Justice? Which Rationality, MacIntyre rejects the idea that liberal morality is in any way universally true, let alone simply a neutral setting to which we should all default. Nevertheless, he admits that “liberalism is by far the strongest claimant to provide [a neutral tradition independent] ground which has so far appeared in human history and which is likely to appear in the foreseeable future.” In other words, while he rejects that liberalism is either morally true in a strong sense, or even just a neutral “political rather than metaphysical” conception that can exist atop or alongside other doctrines, he concedes that it comes closer than rivals. MacIntyre insists that critics must learn from and admire the richness of the liberal tradition while liberals must accept that theirs is only one moral tradition amongst many, with a “problematic internal to it, its own set of questions which by its own standards it is committed to resolving.”

While this may be possible for liberalism at its most morally reflective, MacIntyre remained convinced it was not possible for capitalism. In Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity, he lampoons pro-capitalist economists for their ideological myopia, noting that for the “large majority of academic economists, the gross inequalities and recurring unemployment and regeneration of poverty that result from even the best economic policies are effects that must be accepted for the sake of the benefits of long-term growth and with it worldwide reduction in the harshest poverty in underdeveloped countries.” In other words, the very Leninist solution to the problems created by capitalism is more capitalism, ever and always. MacIntyre remained convinced that liberalism likely lacked the resources necessary to adequately criticize the mode of production with which it came into the world. More likely, a “Thomist revival and the critique of capitalism that Marx made possible” would have to be mined for “new possibilities.”

Left and Right Receptions of MacIntyre

MacIntyre always considered himself a man of the left, insisting that his Aristotelianism was “revolutionary” rather than reactionary, and musing that well into life he still wished to see every rich person hanged. Even in After Virtue, he lampooned the “ideological” character of conservative thinking and acidly mused that any tradition that became Burkean was already functionally dead. MacIntyre had little time for nationalism, musing that being asked to die for the nation state was on a par with being asked to die for the telephone company. In “A Partial Reply to My Critics,” he charged that nationalism was, by and large, a poor man’s golden calf, often deployed by state officials to mobilize their people into defending causes that were contrary to the common good.

MacIntyre always considered himself a man of the left, insisting that his Aristotelianism was “revolutionary” rather than reactionary.

Nevertheless, the depth and scope of MacIntyre’s critique of liberalism and its grounding in classical and Christian sources have made it a fertile source of inspiration for many on the right. By and large, they tend to follow Mahoney’s misguided footsteps in lauding his rejection of liberalism, while insisting “MacIntyre’s brand of ‘Marxism’ is not in the end all that compelling, nor even truly Marxist—although it has had a troubling influence on young Catholics of the traditionalist sort.” That MacIntyre was more sympathetic to liberalism than to capitalism, seeing the former as partially redeemable and the latter as beneath contempt, is largely ignored by his right-wing readers and interpreters.

That MacIntyre was more sympathetic to liberalism than to capitalism, seeing the former as partially redeemable and the latter as beneath contempt, is largely ignored by his right-wing readers and interpreters.

More interesting has been the recent attraction of his work to a variety of post-liberal thinkers, some of whom have been variably willing to accept aspects of the critique of capitalism. In Compact magazine, Nathan Pinkoski argues that the ascendance of post-liberal readings of MacIntyre owes much to the failure of the left to appropriate his work. This is despite MacIntyre’s own inclinations. This has meant that the primary school of thought carrying his legacy forward has been the right, making him a reluctant godfather to post-liberal thinking. Acknowledging that MacIntyre did everything he could to disown right-wing interpretations of the right, Pinkoski observes that, though being ignored “by the left, the MacIntyrean Aristotelian paradigm ended up getting picked up by a new American right that was critical of both capitalism and liberalism. It is impossible to understand the new postliberal right without discussing Alasdair MacIntyre.”

Today, the post-liberal right is the chief ideological vehicle pushing MacIntyrean-sounding themes into the public consciousness.

Pinkoski overstates his case that MacIntyre has been ignored by the left. Indeed, over the last few years there has been an enormous surge of interest in his work. Recent books like Jason Hannan’s Trolling Ourselves To Death and Jason Blakely’s Lost In Ideology cite him as a major influence. MacIntyre is a consistent presence on the pages of Jacobin and The Nation. But Pinkoski is no doubt correct that today, the post-liberal right is the chief ideological vehicle pushing MacIntyrean-sounding themes into the public consciousness. That they often dull down the sharp ends of his contempt for capitalism into R.R Reno style bloviations—that the chief class war being waged in this country is between elites defending gay marriage and ordinary people opposed to it—doesn’t change that.

Taking MacIntyre’s Work to Heart

I believe that liberals can successfully answer MacIntyre’s critiques while acknowledging their substance. Without a doubt, there is a form of possessive individualist liberalism that is committed to a crude view of human beings as competitive hedonists who each aspire to be number one in their own office cubicle. In recent years, this form of liberalism has mutated into neoliberalism, a doctrine which, contra the rosy impulses of post-liberals, has been very easily married to right-wing populists’ cute obsessions with racial superiority, gender inequality, and keeping Andrew Tate out of jail. This should come as no surprise given possessive individualist liberalism’s competitive, meritocratic orientation synthesizes well with the right’s historic concerns for authority and hierarchy.

But there are other forms of liberalism which have long been committed not only to the public but “common” good, as MacIntyre understood it. Liberty, equality, and above all fraternity or solidarity, of course, entered the political lexicon through the bourgeois revolutions. MacIntyre is right to charge neoliberalism with failing to offer a sense of hope for the future, relying instead on the nihilism of capitalist realism. But as Samuel Moyn notes in Liberalism Against Itself, this considered hopelessness is by no means endemic to liberalism. In their tradition’s early years, liberals were revolutionaries who truly thought the world ought to be remade anew, to make it work better for the common man. Liberal socialists like John Stuart Mill insisted that a more cooperative, democratic economy would foster a greater sense of community and solidarity between people and called for an end to meritocratic mythologies.

Moreover, it isn’t clear to me that liberalism doesn’t have an advantage over moral “rival” traditions in creating greater space for the very pluralism MacIntyre commends. Theoretically, liberals have often given in to forms of crude, imperialist “abstract” universalism of the sort one still hears from ride-or-die centrists. But they have also stressed that tolerance and even the celebration of difference are necessary, precisely because of the universal truth that people are concretely different. What is good for D.H. Lawrence may not be good for Greta Thunberg. A decent liberal society creates space for both to achieve the forms of flourishing appropriate to them. MacIntyre himself seems to have moved in this direction by the time of Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity, where he celebrates the idiosyncrasy of distinctly individual kinds of lives. It is not clear to me that anything but a kind of liberal temperament and politics can enable such variety.

Liberals would all benefit from taking MacIntyre’s work to heart.

Nevertheless, liberals would all benefit from taking MacIntyre’s work to heart, especially his deep understanding of how the distortions of capitalism produce nihilistic and egocentric dispositions that destabilize and profoundly banalize the kind of dignified societies we aspire to. For that and much else, we say rest in peace, MacIntyre—the greatest moral philosopher has finally ceased to philosophize and has gone to his well-deserved rest.

Matt McManus is a Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Michigan. He is the author of The Political Right and Equality and recently The Political Theory of Liberal Socialism, among other books.